Low

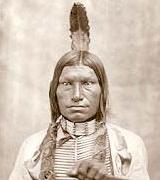

Dog (Sunka Kucigala) was a young

Oglala

at the time of his transfer to the Standing Rock Agency in the

summer

of 1881, giving his age as 34 [born ca. 1847]. William Garnett

refers

to him as an "upstart". He surrendered in 1881, he lived on the

Standing Rock Reservation (not Cheyenne River). He was still on

Standing Rock as late as 1920.

Low

Dog (Sunka Kucigala) was a young

Oglala

at the time of his transfer to the Standing Rock Agency in the

summer

of 1881, giving his age as 34 [born ca. 1847]. William Garnett

refers

to him as an "upstart". He surrendered in 1881, he lived on the

Standing Rock Reservation (not Cheyenne River). He was still on

Standing Rock as late as 1920.

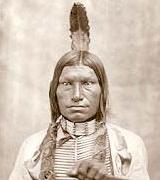

This powerful

and respected warrior, born in

1846, became a war chief at age 14. In 1876 he joined Sitting

Bull's

war party on the Little Bighorn. A Minicauju Chief; he fought

against

Reno and Custer; his full brother was killed in the battle. Low

Dog's

account of the battle is one of history's best known.

"At the time we Oglalas had no thought that we would ever fight

the

whites. Then I heard some people talking that the chief of the

white

men wanted the Indians to live where he ordered and do as he

said, and

he would feed and clothe them. I was called into council with

the chief

and wise men, and we had a talk about that. My judgement was ,

why

should I allow any man to support me against my will anywhere,

so long

as I have hands and so long as I am an able man, not a boy.

I said, Why should I be kept as a humble man, when I am a brave

warrior

and on my own lands? The game is mine, and the hills,and the

valleys,

and the white man has no right to say where I shall go, or what

I shall

do. If any white man tries to destroy what is mine,or take what

is

mine, or take my lands, I will take my gun, get on my horse, and

go

punish him."

“Why should I be kept as a humble man, when I am a brave

warrior and on my own lands? The game is mine, and the hills,

and the

valleys, and the white man has no right to say where I shall go,

or

what I shall do. If any white man tries to destroy what is

mine,or take

what is mine, or take my lands, I will take my gun, get on my

horse,

and go punish him.”

I called to my men:

“This is a good day to die. Follow me.”

Low

Dog's Story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn

We were

in

camp near Little Big Horn river. We had lost some horses, and an

Indian

went back on the trail to look for them. We did not know that

the white

warriors were coming after us. Some scouts or men in advance of

the

warriors saw the Indian looking for the horses and ran after him

and

tried to kill him to keep him from bringing us word, but he ran

faster

than they and came into camp and told us that the white warriors

were

coming. I was asleep in my lodge at the time. The sun was about

noon

(pointing with his finger). I heard the alarm, but I did not

believe

it. I thought it was a false alarm. I did not think it possible

that

any white men would attack us, so strong as we were. We had in

camp the

Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and seven different tribes of the Teton

Sioux a

countless number. Although I did not believe it was a true

alarm, I

lost no time getting ready. When Igot my gun and came out of my

lodge

the attack had begun at the end of the camp where Sitting Bull

and the

Uncpapas were. The Indians held their ground to give the women

and

children time to get out of the way. By this time the herders

were

driving in the horses and as I was nearly at the further end of

the

camp, I ordered my men to catch their horses and get out of the

way,

and my men were hurrying to go and help those that were

fighting.

When the fighters saw that the women and children were

safe they

fell back. By this time my people went to help them, and the

less able

warriors and the women caught horses and got them ready, and we

drove

the first attacking party back, and that party retreated to a

high

hill. Then I told my people not to venture too far in pursuit

for fear

of falling into an ambush. By this time all the warriors in our

camp

were mounted and ready for fight, and then we were attacked on

the

other side by another party. They came on us like a thunderbolt.

I

never before nor since saw men so brave and fearless as those

white

warriors. We retreated until our men got all together, and then

we

charged upon them. I called to my men, "This is a good day to

die:

follow me." We massed our men, and that no man should fall back,

every

man whipped another man's horse and we rushed right upon them.

As we

rushed upon them the white warriors dismounted to fire, but they

did

very poor shooting. They held their horses reins on one arm

while they

were shooting, but their horses were so frightened that they

pulled the

men all around, and a great many of their shots went up in the

air and

did us no harm. The white warriors stood their ground bravely,

and none

of them made any attempt to get away. After all but two of them

were

killed, I captured two of their horses. Then the wise men and

chiefs of

our nation gave out to our people not to mutilate the dead white

chief,

for he was a brave warrior and died a brave man, and his remains

should

be respected.

Then I turned around and went to help fight the other white

warriors,

who had retreated to a high hill on the east side of the river.

. . . I

don't know whether any white men of Custer's force were taken

prisoners. When I got back to our camp they were all dead.

Everything

was in confusion all the time of the fight. I did not see Gen.

Custer.

I do not know who killed him. We did not know till the fight was

over

that he was the white chief. We had no idea that the white

warriors

were coming until the runner came in and told us. I do not say

that

Reno was a coward. He fought well, but our men were fighting to

save

their women and children, and drive them back. If Reno and his

warriors

had fought as Custer and his warriors fought, the battle might

have

been against us. No white man or Indian ever fought as bravely

as

Custer and his men. The next day we fought Reno and his forces

again,

and killed many of them. Then the chief said these men had been

punished enough, and that we ought to be merciful, and let them

go.

Then we heard that another force was coming up the river to

fight us .

. . and we started to fight them, but the chief and wise men

counseled

that we had fought enough and that we should not fight unless

attacked,

and we went back and took our women and children and went away.

This ended Low

Dog's narration,

given in the hearing of half a dozen officers, some of the

Seventeenth

Infantry and some of the Seventh Cavalry—Custer's regiment. It

was in

the evening; the sun had set and the twilight was deepening.

Officers

were there who were at the Big Horn with Benteen, senior captain

of the

Seventh, who usually exercised command as a field officer, and

who,

with his battalion, joined Reno on the first day of the fight,

after

his retreat, and was in the second day's fight. It was a strange

and

intensely interesting scene. When Low Dog began his narrative

only

Capt. Howe, the interpreter, and myself were present, but as he

progressed the officers gathered round, listening to every word,

and

all were impressed that the Indian chief was giving a true

account,

according to his knowledge. Someone asked how many Indians were

killed

in the fight, Low Dog answered, "Thirty—eight, who died then,

and a

great many—I can't tell the number>—who were wounded and died

afterwards. I never saw a fight in which so many in proportion

to the

killed were wounded, and so many horses were wounded. "Another

asked

who were the dead Indians that were found in two tepees five in

one and

six in the other—all richly dressed, and with their ponies,

slain about

the tepees. He said eight were chief killed in the battle. One

was his

own brother, born of the same mother and the same father, and he

did

not know who the other two were.

The question was asked, "What part did Sitting Bull take in the

fight?"

Low Dog is not friendly to Sitting Bull. He answered with a

sneer: "If

someone would lend him a heart he would fight." Then Low Dog

said he

would like to go home, and with the interpreter he went back to

the

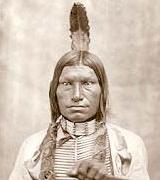

Indian camp. He is a tall, straight Indian, thirty-four years

old, not

a bad face, regular features and small hands and feet. He said

that

when he had his weapons and was on the war-path he considered no

man

his superior; but when he surrendered he laid that feeling all

aside,

and now if any man should try to chastise him in his humble

condition

and helplessness all he could do would be to tell him that he

was no

man and a coward; which, while he was on the war-151;path he

would

allow no man to say and live.

He said that when he was fourteen years old, he had his first

experience on the war-path: "I went against the will of my

parents and

those having authority over me. It was on a stream above the

mouth of

the Yellowstone. We went to war against a band of Assiniboins

that were

hunting buffalo, and I killed one of their men. After we killed

all of

that band another band came out against us, and I killed one of

them.

When we came back to our tribe I was made a chief, as no Sioux

had ever

been known to kill two enemies in one fight at my age, and I was

invited into the councils of the chief and wise men. At that

time we

had no thought that we would ever fight the whites. Then I heard

some

people talking that the chief of the white men wanted the

Indians to

live where he ordered and do as he said, and he would feed and

clothe

them. I was called into council with the chief and wise men, and

we had

a talk about that. My judgment was why should I allow any man to

support me against my will anywhere, so long as I have hands and

as

long as I am an able man, not a boy.

Little I thought then that I would have to fight the white man,

or do

as he should tell me. When it began to be plain that we would

have to

yield or fight, we had a great many councils. I said, why should

I be

kept as an humble man, when I am a brave warrior and on my own

lands?

The game is mine, and the hills, and the valleys, and the white

man has

no right to say where I shall go or what I shall do. If any

white man

tries to destroy my property, or take my lands, I will take my

gun, get

on my horse, and go punish him. I never thought that I would

have to

change that view. But at last I saw that if I wished to do good

to my

nation, I would have to do it by wise thinking and not so much

fighting. Now, I want to learn the white man's way, for I see

that he

is stronger than we are, and that his government is better than

ours."

Return to

Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Return to

Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Compiled by: Glenn Welker

This site has been accessed over 10,000,000 times since

February 8,

1996.

![]() Return to

Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Return to

Indigenous Peoples' Literature