Image from World Wisdom

Whenever, in the course of the daily hunt, the hunter comes upon a scene that is strikingly beautiful or sublime -- a black thundercloud with the rainbow's arch above the mountain, a white waterfall in the heart of a green gorge, a vast prairie tinged with the blood-red of the sunset -- he pauses for an instant in an attitude of worship.

He sees no need for setting apart one day in seven as a holy day, because to him all days are God's days.

The first American mingled with his pride a singular humility. Spiritual arrogance was foreign to his nature and teaching. He never claimed that the power of articulate speech was proof of superiority over the dumb creation; on the other hand, it is to him a perilous gift.

Every age, every race, has its leaders and heroes. There were over sixty distinct tribes of Indians on this continent, each of which boasted its notable men. The names and deeds of some of these men will live in American history, yet in the true sense they are unknown, because misunderstood. I should like to present some of the greatest chiefs of modern times in the light of the native character and ideals, believing that the American people will gladly do them tardy justice.

It is matter of history that the Sioux nation, to which I belong, was originally friendly to the Caucasian peoples which it met in succession-first, to the south the Spaniards; then the French, on the Mississippi River and along the Great Lakes; later the English, and finally the Americans. This powerful tribe then roamed over the whole extent of the Mississippi valley, between that river and the Rockies. Their usages and government united the various bands more closely than was the case with many of the neighboring tribes.

During the early part of the nineteenth century, chiefs such as Wabashaw, Redwing, and Little Six among the eastern Sioux, Conquering Bear, Man-Afraid-of-His-Horse, and Hump of the western bands, were the last of the old type. After these, we have a coterie of new leaders, products of the new conditions brought about by close contact with the conquering race.

This distinction must be borne in mind -- that while the early chiefs were spokesmen and leaders in the simplest sense, possessing no real authority, those who headed their tribes during the transition period were more or less rulers and more or less politicians. It is a singular fact that many of the "chiefs", well known as such to the American public, were not chiefs at all according to the accepted usages of their tribesmen. Their prominence was simply the result of an abnormal situation, in which representatives of the United States Government made use of them for a definite purpose. In a few cases, where a chief met with a violent death, some ambitious man has taken advantage of the confusion to thrust himself upon the tribe and, perhaps with outside help, has succeeded in usurping the leadership.=

| 1. AMERICAN HORSE 2. CRAZY HORSE 3. DULL KNIFE 4. GALL 5. HOLE-IN-THE-DAY 6. CHIEF JOSEPH 7. LITTLE CROW 8. LITTLE WOLF 9. RAIN-IN-THE-FACE 10. RED CLOUD 11. ROMAN NOSE 12. SITTING BULL 13. SPOTTED TAIL 14. TAMAHAY 15. TWO STRIKE |

Who

was

Charles Eastman?

(Slide Show)

Secondary bibliography on Charles Eastman

Biographical sketch

at the Native Authors site.

Bibliography and

information by Paul Reuben at his PAL site

Pictures and quotations

from the National Library of Medicine site.

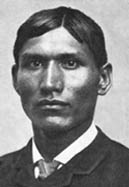

A slideshow with pictures

at the commercial site World Wisdom includes pictures of

Eastman and a biographical sketch.

Biographical sketch of

Eastman's wife Elaine Goodale at The National Cyclopedia of

American Biography

Works Available Online

Note: The University of

Virginia

E-text Center now has free versions of Eastman's works

available

for download in PalmOS and Microsoft Reader format.

Indian Boyhood (1902)

(Virginia)

Red Hunters and the Animal

People (1904)

The Madness of Bald Eagle

(1905) (Virginia)

Old Indian Days (1907)

(Virginia)

Wigwam Evenings (with

Elaine Goodale Eastman) (1909)

The Soul of the Indian

(1911) Google Books.

Indian Child Life (1913)

Indian Scout Talks (1914)

The Indian To-Day (1915)

Google Books.

From the Deep Woods to

Civilization(1916) Google Books.

Indian Heroes and Great

Chieftains (1918)

Essays and Speeches (all

from Google Books)

"Address to the Mohonk

Conference" (1907) Google Books.

"The Sioux Mythology"

Popular Science Monthly, 1895. Google Books.

"What Can the Out-Of-Doors

Do for Our Children?" Education, 1920-21

Letter about Sitting Bull

in Moorehead's The American Indian in the United States

"The Indian as a Citizen,"

Lippincott's, 1914

"The North American

Indian" from Spiller's Papers on Inter-Racial Problems, 1911

![]() Return to

Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Return to

Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Compiled by: Glenn Welker

This site has been accessed over 10,000,000 times since

February 8,

1996.